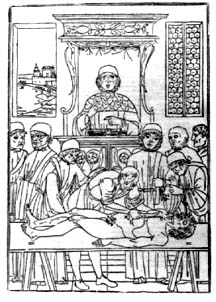

Left: Frontispiece to work by Mondino (1493); Right: Frontispiece to work by Mondino (1550).

Previous to Vesalius and his contemporaries, the study of anatomy consisted of a reading of the works of Galen, the great Roman biologist/physician who wrote in Greek, in the 2nd century AD. You can examine the following image of the frontispiece (the decorated page next to the title page) of a work preceding Vesalius, by Mondino (1493), and a reworking of that scene by Ketham (1550):

Left: Frontispiece to work by Mondino (1493); Right: Frontispiece to work by Mondino (1550).

You will note in these images, especially that of Ketham which has the most elements, the following aspects:

What does this image mean? At first glance it might seem that (1) and (2) above are two aspects of a linked process, but in the pre-Vesalian practice, they were not. The Professor read from a work by Galen, which contained both interesting insights and many mistakes concerning human anatomy. Galen, once he had retired as physician to the gladiators, had little access to human cadavers, so he used the next best thing: equivalent organs from mammals such as oxen, pigs, and the like. But these are not identical, and occasionally quite dissimilar in fine structure.

As the professor read from Galen (a work by some 13 centuries old by the time these images were made), the demonstrator-dissector (the barber-surgeon) tried, sometimes desparately, to find the body part being described. But where Galen was in error (as in certain structures of the brain and heart), the search was in vain. But little matter, the authority was the text, not the body, and the students would learn to repeat Galen as tradition required.

Now, let's consider Vesalius. Here is the frontispiece of his 1543 work on the De Humani Corporis Fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body):

This image is more difficult to analyze, since it so much more crowded. In fact, its a bit of a mob scene, complete with various animals wandering about in the full image, which you can access here in a reproduction of the original etching (black and white wood cut), (its a separate file as it would be too large and take too long to load with this page), or here in a reproduction of a hand tinted version from a copy probably owned by the Emperor Charles V. But in the key central part of the frontispiece above, note the following:

Here then is one important element of the scientific revolution in biology (as in other aspects of science): the authority of tradition, and in particular of classical works, however well founded and convincing they may have been in the past, is replaced by novel ideas based on a re-examination of nature itself.

Now, let's look at some of the drawings which Vesalius produced, drawings which are striking for their realistic depictions of the human body and for their iconology (associated symbolic elements embedded in images).